Histoire

LA MÈRE DE TOUTES LES TRANSATLANTIQUES

C'est la plus ancienne course au large en solitaire au monde.

De 1960 à 2024, elle est à l'origine de la voile océanique telle qu'on la connaît aujourd'hui.

40 JOURS

12 HEURES

30 MIN

1960

Les tout débuts

PLYMOUTH

NEW YORK

5 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

FRANCIS CHICHESTER

BATEAU :

GYPSY MOTH |||

The Transat naît d’un pari entre une poignée de marins britanniques pour savoir s’ils sont capables de traverser l’Atlantique en solitaire et en combien de temps. Parmi eux, Sir Francis Chichester et Blondie Hasler. Le concept imaginé en 1960 est d’abord critiqué, tourné en dérision et considéré comme insensé. L’idée même d’une course à la voile en solitaire est révolutionnaire et quasiment inédite à l’époque, mais ces hommes ont un objectif et ils sont déterminés.

Blondie Hasler cherche des sponsors pour la course, mais en 1959, personne n’est prêt à le soutenir (lui et son idée folle). Finalement, le journal The Observer franchit le pas, et en 1960, sous la direction du Royal Western Yacht Club of England, est organisée la course transatlantique en solitaire “Observer Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race”, autrement dit l’OSTAR.

Étonnamment 115 personnes manifestent leur intention de participer à la course, 50 déposent une demande d’inscription, mais seuls huit bateaux sont officiellement inscrits et cinq prennent le départ de Plymouth.

A l’époque, il n’y a pas de système de navigation par satellite, mais uniquement des compas et des sextants. Privés des moyens technologiques d’aujourd’hui, les marins n’ont alors que peu d’occasions d’envoyer des nouvelles à la terre et au fil des jours l’inquiétude grandit. Mais après 40 jours, 12 heures et 30 minutes de mer, Francis Chichester arrive le premier à New York. “Chaque fois que j’essayais de faire route direct sur New York, le vent se mettait à souffler pile dans le nez de Gipsy Moth”, explique Chichester à son arrivée. “C’était comme essayer d’atteindre une porte avec un homme dressé sur votre passage, un tuyau d’arrosage pointé sur vous “.

Jean Lacome est le dernier à rejoindre Big Apple en 74 jours.

Cette première édition en 1960 est la seule à se courir sans multicoque et la seule (et unique à ce jour) avec une arrivée à New York.

27 JOURS

03 HEURES

56 MIN

1964

Une légende est née

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

13 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

ERIC TABARLY

BATEAU :

PEN DUICK II

La deuxième OSTAR en 1964 est un tremplin pour l’un des plus éminents personnages de la navigation en solitaire : Eric Tabarly. En 1960, Francis Chichester avait bouclé l’épreuve en 40 jours. Quatre ans plus tard, le lieutenant de marine Tabarly, remporte la course en seulement 27 jours, 3 heures et 56 minutes à bord de son ketch de 44 pieds, Pen Duick II.

À son arrivée à Newport, dans le Rhode Island, il n’est pas au courant de sa victoire. Il n’a pas utilisé sa radio pendant la course, et comme si cela n’avait rien d’extraordinaire, il dévoile à son arrivée que son système de pilote automatique n’a fonctionné que pendant les 8 premiers jours de course. La performance d’Eric Tabarly contribue largement à populariser la voile en France, d’où seront issus les années suivantes les plus grands vainqueurs de courses en solitaire et de The Transat.

Parmi les anecdotes marquantes de cette édition, voici celle rapportée dans la presse le 3 juin 1964, par les mots du skipper d’Ilala, Mike Ellison. « J’avais commencé une série de contacts radio avec David Lewis, sur Rehu Moana. Je trouvais cela à la fois intéressant et encourageant de savoir les problèmes qu’il rencontrait, et la météo. Un soir, je lui demandais ce qu’il pensait de mon pain qui commençait à moisir. Il m’a dit qu’il aurait peut-être un effet laxatif. Après cet appel, je me suis demandé s’il essayait de m’aider ou de me ralentir. J’ai continué à manger mon pain jusqu’en Amérique ».

25 JOURS

20 HEURES

33 MIN

1968

L’invention (et l’interdiction) du routage

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

35 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

GEOFFREY WILLIAMS

BATEAU :

SIR THOMAS LIPTON

La course prend un tournant international avec un total de 35 compétiteurs venus de Suède, d’Allemagne, des États-Unis et d’Afrique du Sud en plus des habituels skippers anglais et français. Cette année là, le nord de l’Atlantique est balayé par une énorme dépression générant des vents de plus de 60 nœuds.

De nombreux concurrents se mettent en panne, sous tourmentin seul pour affronter de terribles conditions. Un seul participant creuse l’écart, en profitant des règles de course qui n’interdisent alors pas le routage météo. Geoffrey Williams, sur Sir Thomas Lipton, est le premier à utiliser le routage météo en course. Grâce à une grosse radio haute fréquence, il peut communiquer avec des météorologistes basés à Bracknell.

Averti de la tempête, Williams choisit une route au nord. Il évite ainsi le plus gros de la dépression et gagne environ 300 milles sur ses concurrents. Williams remporte finalement la course, mais sur les éditions suivantes le routage météo ne sera plus autorisé. En 1968, pas moins de 13 multicoques figurent sur la ligne de départ. Parmi eux, un “géant” de 20 mètres (Pen Duick IV) skippé par Éric Tabarly. Mais le trimaran souffre d’un manque de préparation suite aux grèves de mai 68 et le Français est contraint à l’abandon.

Avant la tempête, le Britannique Eric Willis, à bord de Coila, contracte une infection bactérienne qui lui fait perdre connaissance. Il réussit pus tard à recoller les morceaux à partir de ce qu’on lui a dit et se souvient qu’il avait appelé radio Halifax avec une estimation de sa position. Halifax lui demande de rester en ligne, mais il retourne s’allonger dans sa banette et coupe la communication. Des recherches sont alors lancées et deux hélicoptères de secours du programme Apollo Space sont envoyées sur zone à travers un épais brouillard. Ils réussissent à apercevoir la peinture orange fluo du pont du 60 pieds Coila. Des hommes plongent pour monter à bord du bateau et administrer au skipper un traitement médical d’urgence. Un navire de secours remorque le trimaran jusque Portland dans le Maine avec un équipier à bord qui, selon Willis “a rangé mon bateau et n’a même pas bu de mon whisky”.

20 JOURS

13 HEURES

15 MIN

1972

L’âge des multicoques

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

55 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

ALAIN COLAS

BATEAU :

PEN DUICK IV

Le trimaran d’Éric Tabarly, Pen Duick IV, revient dans la course avec à la barre Alain Colas, autre figure de la voile en solitaire française. Sur les 55 participants, 12 sont français, dont les trois premiers arrivants.

Les marins cherchent à aller de plus en plus vite, et la taille moyenne des bateaux augmente rapidement. Signe d’une nouvelle ère, les règles imposent désormais une taille minimale, pour dissuader les inscriptions peu sûres, mais pas de taille maximale. La star des monocoques est ainsi Vendredi Treize (skippé par Jean-Yves Terlain), un trois mâts goélette de 39 mètres, immense pour un skipper en solitaire.

Marie-Claude Fauroux (Aloa VII) est la première femme à boucler le parcours. Elle termine en 14e position après 33 jours de mer. Sir Francis Chichester, alors âgé de 70 ans, prend le départ à bord de Gipsy Moth V, mais ne parvient pas à boucler le parcours de ce qui sera sa dernière course. Il meurt quelques mois plus tard. Peter Crowther fait quant à lui la traversée la plus longue de l’histoire (88 jours) avec son vieux bateau Golden Vanity, un côtre aurique de 66 ans.

23 JOURS

20 HEURES

12 MIN

1976

Controverses et tragédies

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

125 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

ERIC TABARLY

BATEAU :

PEN DUICK VI

Avant même le départ, la tempête fait rage. La controverse explose autour de la participation d’Alain Colas sur le gigantesque monocoque Club Méditerranée, long de 236 pieds (72 mètres). Il est alors difficile d’imaginer qu’un bateau de cette taille puisse être skippé en toute sécurité par un seul homme, sans représenter un danger pour lui-même comme pour les autres navires. Et avec 125 bateaux inscrits, beaucoup considèrent que l’organisation de course perd le contrôle. Le départ est assombri par la mort de la femme de Mike McMullen, électrocutée en aidant Mike à préparer le bateau.

Lors des formalités précédant le départ, on découvre également que l’un des inscrits, David Sandeman, n’a que 17 ans et 176 jours. Ce dernier n’est pas officiellement autorisé à prendre le départ de la course, mais il franchit la ligne après le passage du dernier bateau et s’élance à travers l’Atlantique. A mi-parcours, un chalutier russe le percute la nuit en pleine tempête. Dans la collision, Sanderman démâte, mais les Russes l’aident à réparer pour qu’ils puissent continuer sa route. Sandeman entre ensuite au livre Guinness des Records comme le plus jeune marin à avoir traversé l’Atlantique en solitaire entre Jersey et le Rhode Island.

Plusieurs grosses dépressions se succèdent pendant la course, entraînant le nombre record de 50 abandons. Le Britannique Tony Bullimore est secouru par un proche navire alors que son bateau était en feu, et l’Anglais Mike Flanagan disparaît en mer après être tombé de son bateau Galloping Gael. Sans oublier le triste destin de Mike McMullen à bord de Three Cheers. Pensant que sa femme aurait souhaité le voir traverser l’Atlantique, il prend le départ de la course, mais on ne le reverra jamais.

Eric Tabarly remporte cette édition en 23 jours, 20 heures et 12 minutes. Clare Francis finit 13e et améliore de trois jours le record féminin de la traversée de l’Atlantique en solitaire.

17 JOURS

23 HEURES

12 MIN

1980

Le triomphe des multicoques

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

110 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

PHILIP WELD

BATEAU :

MOXIE

La course est une fois de plus dominée par les multicoques. Les cinq premières places reviennent à des trimarans et l’événement marque la fin de l’équité entre monocoques et multicoques. Suite à l’édition de 1976, les organisateurs imposent une restriction sur la longueur des bateaux, désormais de 56 pieds (17m) maximum, et sur le nombre de participants, limité à 110 bateaux. Quatre vingt dix concurrents prennent le départ de cette 6e édition qui est marquée par une nette baisse de participation des Français, mécontents des nouvelles règles.

La course continue d’innover avec pour la première fois l’utilisation du système de positionnement par satellite Argos. Cette technologie permet de suivre la progression des bateaux à distance et peut aussi être utilisée pour des appels de détresse, une méthode encore largement répandue sur les courses au large aujourd’hui.

L’Américain Phil Weld remporte cette édition, qui n’est que sa deuxième participation. Son trimaran Moxie avait été constuit spécialement pour la course, à la limite des 56 pieds (17 mètres). Il établit un nouveau record en 18 jours (cinq de moins que le précédent) et sa victoire est d’autant plus remarquable qu’il est le doyen de l’épreuve (65 ans). Au total, soixante sept bateaux franchissent la ligne d’arrivée.

16 JOURS

06 HEURES

25 MIN

1984

Les larmes de Poupon

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

91 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

YVON FAUCONNIER

BATEAU :

UMUPRO JARDIN V

Le départ de l’édition 1984 est très animé. Dès le premier jour, la flotte subit une série de démâtages dans des vents très forts et plusieurs skippers obtiennent des compensations de temps pour avoir porté secours à d’autres concurrents. Mais cette année là on ne parle que du chavirage de Philippe Jeantot (Crédit Agricole) au milieu de l’Atlantique, car l’accident pose un problème à l’arrivée.

Philippe Poupon (Fleury Michon) est en effet le premier à couper la ligne d’arrivée à Newport après 16 jours, 11 heures et 55 minutes de course, mais c’est Yvon Fauconnier (Umupro Jardin) qui est déclaré vainqueur pour avoir passé 16 heures à secourir Jeantot. Son temps d’arrivée tombe alors à 16 jours, 6 heures et 25 minutes, soit cinq heures de mieux que Poupon. Philippe Poupon, qui apprend la nouvelle au milieu de la conférence de presse dédiée à sa victoire, ne peut dissimuler son immense déception et fond en larmes.

À l’arrivée, huit des dix premiers concurrents sont français, et seul le 10e bateau n’est pas un multicoque. Ces dix premiers skippers bouclent le parcours en moins de 17 jours. La course devient un sprint transatlantique.

10 JOURS

09 HEURES

15 MIN

1988

Baleines en vue

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

95 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

PHILIPPE POUPON

BATEAU :

FLEURY MICHON

On dénombre 95 participants en 1988. La tendance est alors à l’électronique, aux fichiers météo, et aux pilotes automatiques. Le navigateur en solitaire ne doit plus seulement être un excellent marin et un courageux compétiteur, il doit aussi maîtriser les outils informatiques.

Suite aux conditions exceptionnelles sur l’Atlantique, Philippe Poupon suit une route directe tout au long du parcours, pulvérisant son propre record qui tombe à 10 jours, 9 heures et 15 minutes, soit l’équivalent de la route orthodromique à une vitesse moyenne de 11 nœuds.

Une des plus incroyables histoires de cette édition est celle des nombreuses baleines croisées par la flotte. Mike Birch voit ainsi son trimaran FujiColor sévèrement endomagé suite à une collision contre une d’entre elles. Et quelques jours plus tard, le Britannique David Sellings se retrouve encerclé par un banc de 50 à 60 baleines pendant trois jours, avant de finalement se faire attaquer. Sellings a tout juste le temps d’attraper quelques affaires et de gonfler son radeau de survie avant de voir son bateau couler. “C’était terrifiant”, avoue t’il plus tard à bord du cargo allemand venu lui porter secours.

11 JOURS

01 HEURES

35 MIN

1992

Un parcours semé d’embuches

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

76 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

LOÏCK PEYRON

BATEAU :

FUJICOLOR

Soixante sept bateaux prennent le départ de l’Europe 1 STAR. Loïck Peyron (FujiColor) fait figure de favori au sein des coureurs français qui dominent désormais largement ce sport.

Au cours de la première semaine, aucun leader ne se dessine vraiment. Il est alors difficile d’établir des pronostics, notamment en raison des conditions météorologiques défavorables au départ et parce que la flotte s’éparpille à travers l’Atlantique. Joyon met le cap au Nord, Vatine au Sud et Bourgnon et Peyron se placent au milieu. Il faut presque une semaine pour qu’un leader se démarque. Finalement, Bourgnon, alors leader, casse son rail de grand voile, Arthaud chavire au large de Terre-Neuve et Poupon perd du terrain suite à un problème de dérive. Il n’en reste plus qu’un, Loïck Peyron, qui met le pied sur l’accélérateur et termine en tête avec plus de 24 heures d’avance sur le second bateau.

L’édition 1992 est semée d’embuches : tempêtes, icebergs, cargos, brouillard et baleines.

Voici ce que déclare Jack G. Ganssle le skipper de Amber le 12 juin 1993

“Le vent continuait de monter toute la nuit, sans discontinuer jusqu’en milieu de matinée. J’étais étonné d’apprendre que Philippe Poupon (que certains Américains surnommaient ‘Gray Poupon’) avait abandonné après avoir cassé sa dérive centrale dans le coup de vent. Philippe était considéré comme un des grands favoris de la course. Franck Ravez (Salsa), un jeune Français de 22 ans, avait abandonné lui aussi juste après la tempête car il était trop fatigué pour continuer. La personne qui citait ces abandons en annonça d’autres mais sans donner de noms. Moi je voulais en savoir plus. Qu’étaient devenus mes autres amis ? Est-ce que Corkscrew avançait comme Trevor l’espérait ? Est-ce que Diminutive Nord tenait bon ? Est-ce que Little Fritzz continait de jeter son matériel inutile par dessus bord ?

Je savais qu’il y avait des concurrents partout autour de moi. Fraser était quelque part devant, et David probablement vers le sud-est. Sur le radar de Amber, il n’y avait rien à moins de 16 milles, mais je me sentais pas seul. J’avais le sentiment que même si nous étions tous seuls sur nos bateaux, peut-être à des centaines de milles de distance, nous étions tous ensemble par la pensée”.

10 JOURS

10 HEURES

05 MIN

1996

Un doublé pour peyron

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

53 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

LOÏCK PEYRON

BATEAU :

FUJICOLOR

Les multicoques sont devenues monnaie courante, et on assiste désormais à un match principalement franco-français, en tout cas pour la victoire. Les amateurs reviennent en force dans les petites classes, tandis que les spectateurs attendent sur le podium : Peyron, Bourgnon, Vatine ou Joyon. Ce dernier crée la surprise en optant pour une route encore jamais empruntée depuis le passage de Blondie Hasler en 1960, l’option Nord. Joyon navigue très au Nord, contournant les centres des dépressions qui ralentissent ses adversaires sur la route directe. Il a plus de 300 milles d’avance lorsqu’il atteint Terre-Neuve et rien ne semble pouvoir l’arrêter dans sa course au record. Mais des vents instables viennent le ralentir à seulement 400 milles de l’arrivée. Même mésaventure pour Laurent Bourgnon.

Loick Peyron peut ainsi savourer une seconde victoire. Et bien qu’ayant rencontré des conditions climatiques moins favorables, il réalise un temps très proche du record de Philippe Poupon en 1988. Paul Vatine franchit la ligne quatre heures plus tard.

Voici un extrait du journal de bord de Peter Crowther après que son bateau Galway Blazer ait coulé le 24 juin 1996.

[endif]

“J’étais debout près de la table à cartes quand nous avons tapé dans le creux d’une vague sur l’avant du mât du côté droit avec un bruit horrible. C’était comme si un homme invisible avait défoncé une porte. Un torrent d’eau verte a jailli à l’intérieur du bateau. C’était tellement puissant que j’ai tout de suite su qu’il n’y avait aucun moyen d’arrêter ça.

Je me suis alors précipité pour lancer un appe de détresse à la radio, en hurlant mon nom, ma position et J’ABANDONNE LE NAVIRE ! Dans ce laspe de temps très court, j’avais déjà de l’eau jusqu’aux genoux. J’ai attrapé la balise de détresse et j’ai grimpé dans le radeau de survie. Quand j’ai coupé les amarres et l’écoute de voile d’avant qui gênait le passage, l’étrave était déjà immergée.

Je me suis assis sur le toit dégonflé, absolument trempé. Je me suis dit tout bas : ‘merci pour toutes ces années de navigation. L’intérieur du radeau était très confiné, on ne pouvait pas voir l’horizon. J’ai voulu lancer une fusée mais elles étaient trop vieilles et ne fonctionnaient plus. Génial.

Soudain j’ai vu un avion Nimrod et je l’ai appelé à la VHF. Ils m’ont dit qu’un bateau était parti à ma rencontre, et ils sont gentillement restés en liaison avec moi et le capitaine du bateau.

Peu de temps après, j’ai vu l’’Atlantic Compass’ apparaître à l’horizon. Ils sont venus jusqu’à moi et m’ont lancé un bout. La porte était trois mètres au dessus de moi et il fallait grimper par une échelle. Je savais que je n’étais pas encore en sécurité. Dans la panique, j’ai réalisé que j’avais une jambe derrière l’échelle en corde contre la coque et une jambe devant. J’ai quand même réussi à grimper et j’ai remercié tous les gens que je voyais. Ensuite j’ai appelé ma femme et mes filles et je me suis dit que j’étais heureux d’être en vie. Nous avons partagé notre peine d’avoir perdu un si beau bateau”.

09 JOURS

23 HEURES

21 MIN

2000

L Année Ellen

PLYMOUTH

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

71 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

FRANCIS JOYON

BATEAU :

EURE ET LOIR

Cette édition est considérée comme ‘l’année Ellen’. A tout juste 23 ans, elle est le plus jeune concurrent de la flotte et personne ne l’attend à ce niveau. Sur l’eau, tout le monde est impressionné.

Sept trimarans de 60 pieds prennent le départ de l’Europe 1 New Man STAR 2000, mais la flotte la plus importante est celle des Open 60, qui compte pas moins de 24 inscrits. Un grand nombre d’entre eux participe à la course transatlantique comme entraînement et qualification en vue du Vendée Globe, dont le départ a lieu quelques mois plus tard, en novembre.

Le niveau parmi les Open 60 est très relevé, avec comme favoris Thomas Coville, Michel Desjoyeaux, Yves Parlier, Mike Golding, Roland Jourdain et Dominique Wavre. Mais au final, le vainqueur ne sera aucun d’entre eux. C’est un tout nouveau bateau, qui participe à sa première course, avec à la barre une petite anglaise de 23 ans. Qui aurait parié sur elle ? Au neuvième jour de course, Ellen MacArthur fait un superbe coup météo. Elle repère une molle sur sa route, décide de tirer un bord défavorable vers le nord et prend finalement une avance de 75 milles sur le reste de la flotte, qu’elle gardera jusqu’à l’arrivée. C’est un moment décisif dans sa carrière, car le monde de la voile réalise alors que la jeune anglaise n’est pas là pour faire de la figuration et qu’elle est capable de gagner.

“J’ai appris une chose cette année c’est si vous avez un rêve tout au fond de votre coeur, alors vous pouvez et vous devez le réaliser” - Ellen MacArthur

08 JOURS

08 HEURES

29 MIN

2004

Grande vitesse, risque maximum

PLYMOUTH

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

37 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

MICHEL DESJOYEAUX

BATEAU :

GÉANT

En 2004, l’épreuve se scinde en deux, avec une course réservée uniquement aux skippers professionnels, organisée par OC Sport et baptisée simplement THE TRANSAT, et la traditionnelle OSTAR ouverte aux amateurs et organisée par le Royal Western Yacht Club l’année suivante. The Transat réunit un total de 40 bateaux, monocoques IMOCA 60, monocoques de 50 pieds et multicoques, avec un niveau sans précédent et une compétition acharnée.

Mais une semaine après le départ, une tempête balaye l’Atlantique Nord et fait prendre à la course une tournure spectaculaire, avec une série de sauvetages sans précédent en l’espace de quelques heures. Le bateau de Jean-Pierre Dick fait un 360 dans une vague et démâte dans 50 noeuds de vent. Vincent Riou sur PRB démâte également. Bernard Stamm est contraint d’abandonner son IMOCA 60 Cheminées Poujoulat-Armor Lux après avoir perdu sa quille et chaviré. A l’arrivée à Boston, Michel Desjoyeaux l’emporte à bord de son trimaran ORMA avec seulement trois heures d’avance sur Thomas Coville, après 8 jours de mer. En tête de la flotte IMOCA 60, Mike Golding s’impose à Boston au bout de 12 jours, et aussi trois heures d’avance sur le second, Dominique Wavre.

Bernard Stamm est le plus malchanceux de la flotte. Contraint d’activer sa balise de détresse et d’abandonner son bateau après avoir perdu sa quille et chaviré. Il est secouru par l’équipage d’un petit pétrolier et reviendra plus tard récupérer son IMOCA 60 avec un remorqueur basé à Terre Neuve, à 360 milles de sa position.

12 JOURS

08 HEURES

45 MIN

2008

Un incroyable sauvetage

PLYMOUTH

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

23 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

LOÏCK PEYRON

BATEAU :

GITANA

L’édition 2008 de la plus ancienne course au large en solitaire, baptisée cette année l’Artemis Transat, réunit 13 skippers IMOCA et 10 skippers en Class 40. Trois d’entre eux ne finissent pas la course et Vincent Riou est forcé d’abandonner son IMOCA 60 au milieu de l’Atlantique.

Après une collision avec un requin pélerin, la quille de PRB est gravement endommagée et son skipper ne se sent pas en sécurité à l’approche d’une violente tempête. Il préfère abandonner le bateau. La directrice de course, Sylvie Viant, demande à Loïck Peyron, alors le plus proche concurrent, de se dérouter pour porter secours à Vincent Riou. Afin de simplifier le transfert, Vincent Riou lance son radeau de survie. L’opération, facilitée par les conditions clémentes au moment du sauvetage, est un succès.

Malgré les obstacles, cette édition est la plus rapide depuis la création de l’événement, quarante-huit ans plus tôt. Dès le premier jour, le record sur monocoque détenu par Mike Golding sur Ecover depuis 2004 est menacé. En tête de la flotte, Loïck Peyron est en avance sur le temps du Britannique. Il s’impose finalement en 12 jours, 11 heures et 45 minutes, soit quatre semaines de moins que la première traversée de Sir Francis Chichester en 1960.

08 JOURS

08 HEURES

54 MIN

2016

La renaissance d’une classique

PLYMOUTH

NEW YORK

25 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

FRANCOIS GABART

BATEAU :

MACIF

Le retour de la Transat Anglaise après 8 années d’absence a été un grand succès avec 25 bateaux sur la ligne de départ ainsi que la classe Ultime – dominée par François Gabart – qui a fait son entrée dans la course de manière spectaculaire.

En dehors des Ultime, la seconde grande innovation a été la mise en place d’un pré-départ ralliant Saint Malo à Plymouth. Ce « Warm Up » a été un grand succès, que ce soit pour les marins, les sponsors ou le public français.

Sur cette édition, c’est François Gabart qui a marqué l’histoire après un long bord de portant à travers l’Atlantique et seulement 8 jours et 54 minutes de course. Sa vitesse moyenne - 23,11 nœuds – a été trois fois supérieure à celle du dernier concurrent à franchir la ligne, le Japonais Hiroshi Kitada qui a bouclé sa traversée en 22 jours, 18 heures et trois minutes de course. A bord de son Class 40, Kiho, il est ainsi devenu le premier marin japonais à terminer cette course.

Entre ces deux bateaux, l’épreuve a été fidèle à sa réputation. La majorité des skippers était français mais il y avait cinq marins d’autres nationalités, dont deux allemands et deux britanniques. Six concurrents, soit un quart de la flotte, n’ont pas pu venir au bout de la course, y compris le britannique Richard Tolkien. Blessé, Tolkien a du abandonner son bateau au milieu de l’Atlantique et embarquer à bord d’un cargo. En dehors des Ultimes qui ont évolué sur une route orientée au sud, la plupart des concurrents ont du faire face à une grande tempête dans l’Atlantique Nord et ont également eu à négocier plusieurs dépressions de plus faible intensité.

The Transat bakerly a mis en évidence plusieurs confrontations entre les meilleurs marins au monde. En Ultime, le duel s’est joué Thomas Coville (Sodebo) et François Gabart (Macif). Chez les IMOCA, c’est Vincent Riou et Armel Le Cléac’h qui se sont opposés pendant toute la traversée de l’Atlantique. En Class 40, la bataille a été plus ouverte entre quatre grands marins. Thibaut Vauchel-Camus (Solidaires en Peloton – ARSEP), Louis Duc (Carac), Phil Sharp (Iremys) ainsi qu’Isabelle Joschke (Generali Horizon Mixité) qui a été contrainte à l’abandon. Chez les Multi 50, c’est Gilles Lamiré (Rennes French Tech) qui s’impose devant Lalou Roucayrol (Arkema).

Au delà de ça, le match Banque Populaire / PRB en IMOCA a été celui de deux générations de bateaux et c’est le premier, équipé de foils, qui s’impose face à un PRB dans une configuration plus conventionnelle. L’avance de Le Cléac’h n’était pas très importante mais il a contrôlé Vincent Riou pendant la majorité de la course, démontrant que, même sur un parcours dominé par le près, les foilers pouvaient avoir l’avantage.

L’un des participants à cette édition était un peu à part. Il s’agit de Loïck Peyron, à bord de Pen Duick II, l’ancien bateau d’Eric Tabarly. Son but était de saluer la mémoire de Tabarly en traversant l’Atlantique à bord du bateau vainqueur de la seconde édition, en 1964. Cependant, les vents forts et contraires en ce début d’été 2016 ont eu raison de Pen Duick II qui a rencontré un problème d’étai. Peyron a ainsi été contraint de faire demi-tour après 13 jours de mer alors qu’il était au beau milieu de l’Atlantique.

8 jours 6 heures 53 min 32 sec

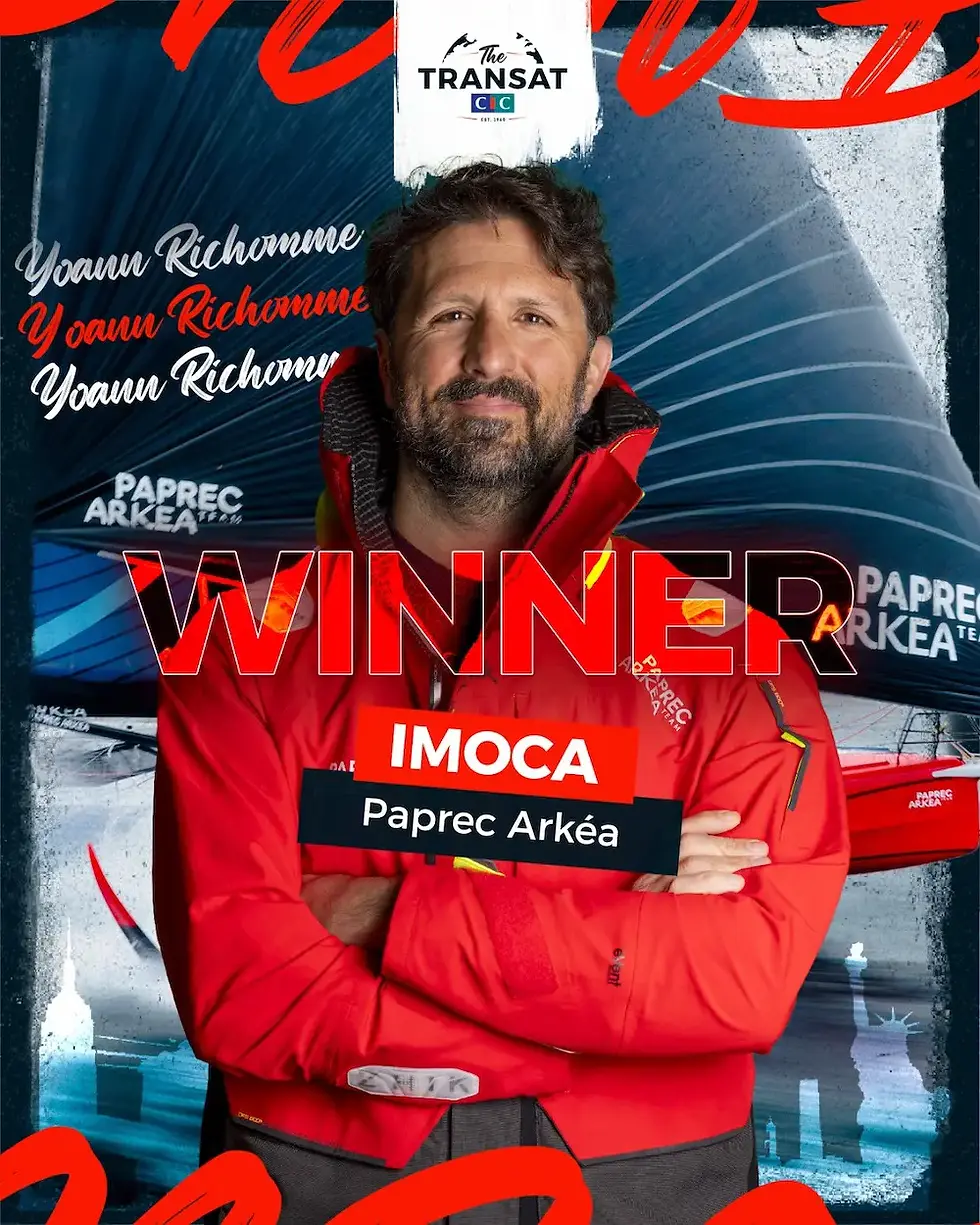

2024

Le retour éclatant d'une course mythique !

LORIENT

NEW YORK

48 CONCURRENTS

VAINQUEUR :

YOANN RICHOMME

BATEAU :

PAPREC ARKEA

Pour la première fois depuis huit ans, la « mère des transatlantiques » est revenue au calendrier de la course au large. Un événement cher aux cœurs de tous les amoureux de la mer tant The Transat CIC a marqué l’histoire. De Sir Francis Chichester à François Gabart, de l’avènement d’Éric Tabarly aux succès de Loïck Peyron, elle a façonné la légende de tant de skippers. Cette nouvelle édition, disputée dans des conditions épiques, n’a pas dérogé à la règle. Fort du soutien du CIC, de Lorient Agglomération, de la Région Bretagne et de nombreux partenaires enthousiastes, la transatlantique a été fidèle à son histoire. Elle a sacré trois grands champions de la discipline, Yoann Richomme (IMOCA), Ambrogio Beccaria (CLASS40), Patrick Isoard (Vintage) et s’est affirmée comme un grand succès populaire. Boris Herrmann et Sam Davies complètent le podium en IMOCA ainsi que Ian Lipinski et Fabien Delahaye en CLASS40.